Heki ryu Bishu Chikurin ha

Tradition and history

About the tradition of our school, as followed by the Barako group. You can read more here. The history of the Heki ryu Bishu Chikurin ha is outlined below:

Japanese kyudo master Kanjuro Shibata XX Sendai (1921-2013) was the twentieth generation in an ancient lineage of arch masters, the last three generations of whom served as Onyumishi (court archer of the imperial court). In the early 1980s, he came to America at the invitation of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, a Tibetan teacher who taught inner warriorship in the tradition of Shambhala Buddhism in the West. That was the beginning of the Zenko school, with Oko as its European counterpart. Zenko and Oko follow the tradition of the Heki ryu Bishu Chikurin ha, an ancient kyudo school straight out of the samurai tradition.

The founder of the Heki ryu (ryu means school) is Heki Yazaemon Nirutsugu, a kyudo master who lived in the 15th century.

One of the heirs to his tradition (the Heki ryu has several divisions) is the Buddhist monk and priest Chikurin-bo Josei, who founded his own school in 1603 under the aegis of the Toshida clan. From it, his disciple Hoshino Kanzaemon formed the Bishu Chikurin ha (ha means department), and his disciple Yoshimi Junsei formed yet another department, the Kishu Chikurin ha. Chikurin-bo Josei’s second son Sasuga completed the mystical standard work Shikan No Sho, started by his father.

Characteristic of the Bishu Chikurin ha is the style of shooting, which (unlike the shomen style practised much more commonly today) is called shamen and, on the one hand, harks back to a ceremonial form of archery associated with Zen meditation and Shinto rituals, while on the other hand retaining many characteristics of the style of hunters and warriors.

Since the death of Kanjuro Shibata XX Sendai (Sendai means: deceased master), the leadership of Zenko and Oko has been in the hands of his son, Kanjuro Shibata XXI Sensei, who in turn trained his son Shibata Munehiro to become the next Onyumishi.

Apart from being a kyudo master, Sendai was also a spiritual teacher. His now also deceased partner Carolyn Kanjuro kept a blog about him that can still be read here.

Traditionally, kyudo has been linked to various philosophical movements. There is a direct link with Zen Buddhism, but relations with the Japanese nature religion Shinto and with Daoism are at least as strong. Kyudo is considered a ‘do’, a path of life. It should be remembered that this is not a road with a goal or end point; as is common thought in the West. The road itself, the eternally ongoing exercise, is the goal: through a constant mirroring of the thoughts, insights and emotions released with each shot, ‘the heart is polished’ (Kanjuro Shibata XX Sendai), without any specifically defined goal: ‘Target: don’t mind!’

Kanjuro Shibata XXI Sensei strongly emphasises the tradition of the Heki ryu Bishu Chikurin ha. Under his influence, the relationship between kyudo and Shinto has been strengthened.

In Japan, kyudo according to the Heki ryu tradition is still practised infrequently. Although meditation can never be completely removed from kyudo practice, contemporary kyudo according to the guidelines of the Japanese Kyudo Federation (JKF) differs from the Heki ryu tradition in a number of ways. In the latter, the emphasis is on meditation and hitting the target is secondary. This is also why there is no grading or ‘dan’ classification. In the words of Kanjuro Shibata XX Sendai Sensei: ‘Kyudo is not a sport. You cannot become the best or the worst at it. Remember that you will always remain a beginner; that’s how you keep an open mind.’

The first Kanjuro Shibata lived on the island of Tanegashima in the 16th century, where he served the Shimazu clan as an arch-builder. In 1574, his son moved to Kyoto, where he began building arches on behalf of the Tokugawa Shoguns. During this period, the concept of the Hama-Yumi, the ‘evil-destroying arch’, which plays an important role in Buddhist and Shintoist purification rituals, emerges. Today’s Kanjuro Shibata, for instance, makes the 59 sacred yumi for the famous Ise temple. This is completely rebuilt once every 20 years, after which the old temple containing the sacred yumi’s is burnt, symbolising constantly renewing life.

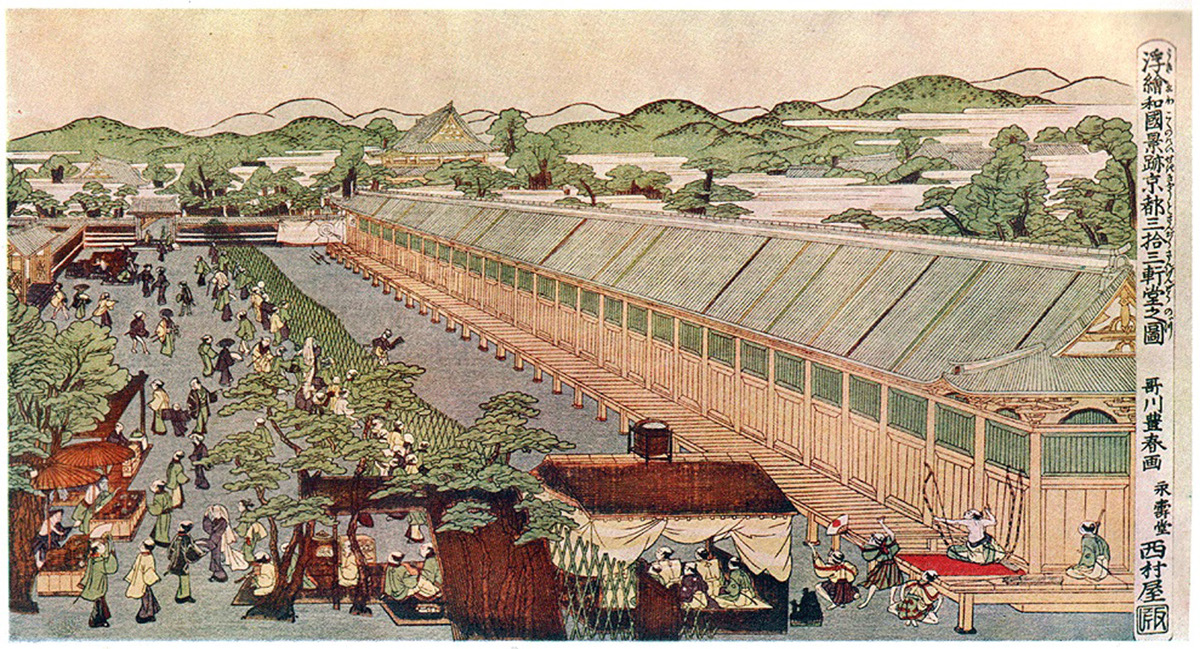

A kyudo practice closely related to the tradition of the Chikurin ha is the Toshiya. From around 1600, the Toshiya has been practised on the west side of the Sanjunsangendo temple in Kyoto. It involves shooting without interruption for 24 hours at a target 120 metres away (the length of the temple) through a corridor 2.20 m wide and 5.6 m high. The record was set in 1686 by a student of Kishu Chikurin founder Yoshimo Junsei, 18-year-old samurai Daihachiro Wasa, who shot 13,053 arrows in 24 hours, of which 8,133 hit the target. This was made possible for him by none other than Hoshino Kanzaemon, founder of the Bishu Chikurin ha, teacher of Yoshima Junsei and the previous record holder with 10,452 shots and 8,000 hits. Seeing that Daihachiro could not continue due to an overly swollen arm, he cut open the swelling himself, allowing his young challenger to continue his shots and break the old record: a great example of honour and service to tradition.

Kanjuro Shibata XX Sendai was declared a living national monument of Japan in 1969. The Shibata family maintained its own dojo in Kyoto, called Tayeshu. This was transferred by Kanjuro Shibata XX Sendai to Kyoto Joshi Dai University as a monument in 1991.

To this day, Kanjuro Shibata XXI Sensei works in the more than 400-year-old workshop behind his home in Kyoto, where he and his son make more than 300 yumis a year, using entirely traditional methods. Nowadays, Shibata Sensei also gives yumi making workshops. He does this both in Japan and in Europe. In these, from splitting the bamboo to finishing with rattan wrapping and leather grip, the building of the yumi is supervised by Sensei and his assistants according to the old methods, with much of the work being done by the participants themselves.